,

,

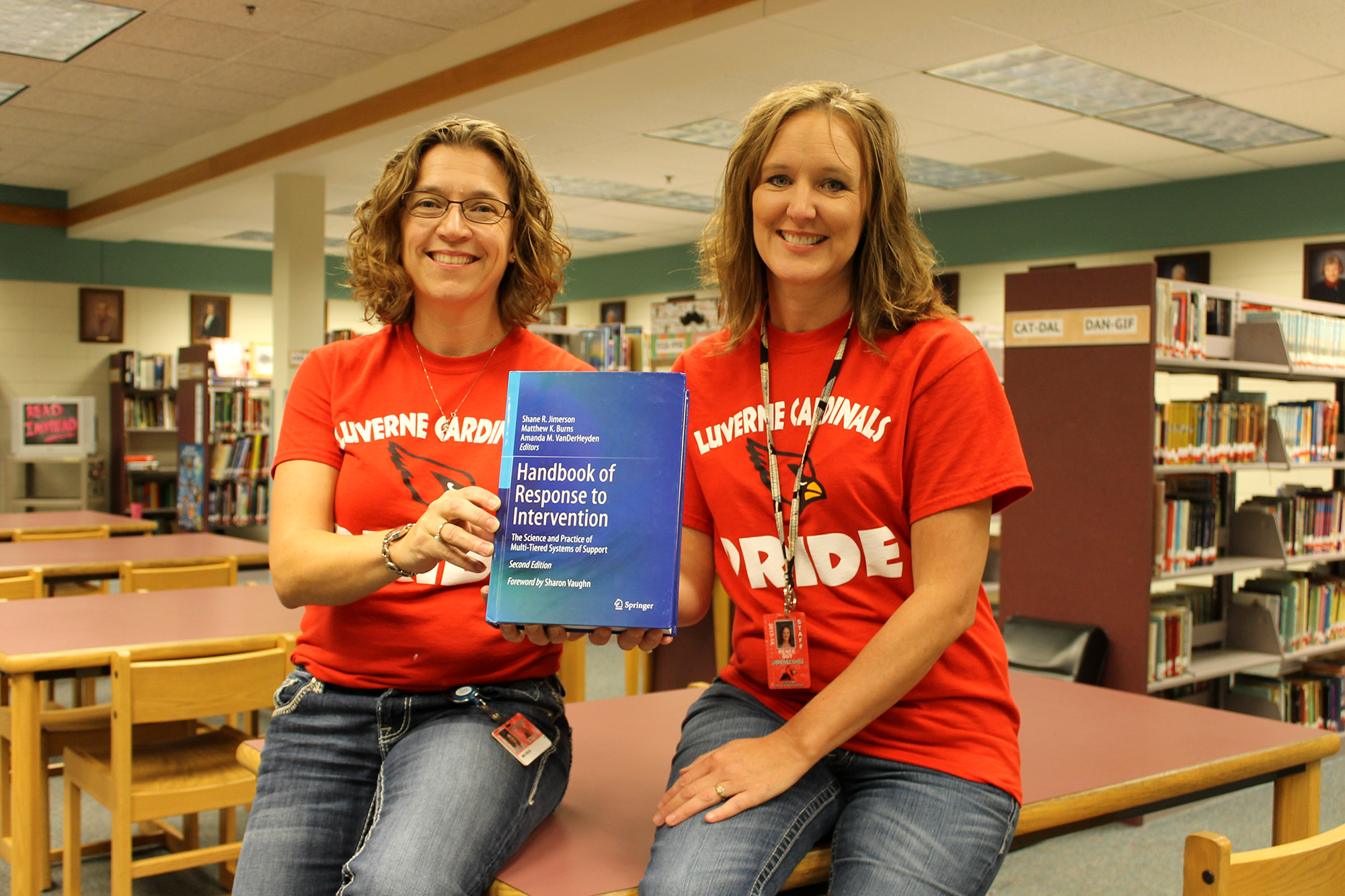

Luverne School Psychologist Renee Guy and teacher Amanda Fields have co-authored a chapter in a textbook for their peers.

The “Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support” is meant for an educational audience and retails for $399.

“It’s a research-based handbook used by universities, public school entities, etc., with their Response To Intervention (RTI) programs,” said Guy, a 1986 LHS grad who has been the district’s psychologist for 17 years.

Luverne’s RTI program targets students who struggle at learning to read.

“The RTI program is designed to help meet the needs of the bottom 20 percent of readers within our district,” said Fields, who has worked in the district’s special education program since 2002.

Fields was the RTI program’s coordinator for its first six years. Today she and Guy play a more advisory role.

RTI began nine years ago

The program’s concept began in 2006 when a team of Luverne elementary instructors attended a training headed by then University of Minnesota education professor Matthew Burns.

As the local group began developing their own program, Guy kept in contact with Burns, who invited her and Fields to write about Luverne’s RTI experience.

The local program was implemented in stages beginning in the fall of 2008.

“It was easy to write because — in a sense — it is about what we did and how we did it,” Guy said.

While the writing wasn’t difficult for the duo, the waiting was.

“It was a really drawn-out process,” Fields said. “You submit the first draft and then we waited a really long time before we got feedback.”

Burns extended the invitation to write about the Luverne program more than three years ago.

“You were selected due to your expertise and the high esteem in which you are held,” Burns wrote in the June 21, 2012, email. “We truly hope you are able to contribute to this important effort.”

Burns, who is now an education professor at the University of Missouri, explained that the handbook’s second edition includes specific program implementation “that is too often missing from the evaluation of education practice.”

In an interview last week, Burns told the Star Herald it is highly unusual for public school personnel to author chapters for a research book.

“We had 106 authors in the handbook, only six of which were school personnel, four other than Renee and Amanda,” he said.

Because rural schools often don’t have the added resources or personnel to devote to interventions, Burns said he wanted to share Luverne’s program as a model for other schools.

Luverne uses existing general education teachers, special educators and specialists to operate the intervention program.

“I was thrilled to include a chapter about Luverne as an example from which rural schools can learn,” Burns said.

Guy and Fields wrote the middle portion of the 22-page chapter, detailing how existing staff members processed specific test and progress data and their selection of specific intervention curriculum.

Lynn Edwards with the University of Minnesota wrote the introduction and conclusion to the chapter.

“We were honored and excited to do it,” Guy said.

Intervention program improves student learning

Three years prior to Luverne Elementary School’s RTI program, its students’ state reading test scores had declined incrementally each year.

After its implementation, the school experienced three consecutive years of increased percentages of students who were now passing the tests.

For its efforts, the Luverne Elementary was presented with the 2011 Profiles of Excellence Award of Distinction from the Minnesota Rural Education Association.

“The book explains this process,” Fields said. “Students work in small groups, 25 minutes a day, four days a week (called Power Hour), and work on phonics, fluency or comprehensive skills.”

Screening and tracking of all students are key components to Luverne’s RTI program.

An RTI team completes a one-minute reading test with each kindergarten-through sixth-grade student three times a year.

Students who are not meeting specific grade-level reading benchmarks are placed into small groups.

In the daily 25-minute Power Hours, student progress is closely monitored with RTI team members detailing results on a common spreadsheet.

Student groups are shuffled as students become proficient in one or more of the intervention areas.

“During the first year of interventions, we had a number of students in need of phonics intervention,” Guy and Fields wrote in their chapter.

“As students moved through the interventions, we have noted a decreased need for phonics in the upper grade levels.”

As Luverne elementary continues to implement its RTI program, coordinators have experienced a 50 percent drop in special education referrals. Those students’ learning needs are being met in the regular classroom setting.

“We feel that because of the RTI program, we have fewer children in special education and receiving special education services,” Guy said.

“We know when kids are not making progress that’s the time we need to look at (special education) assessment.”