,

,

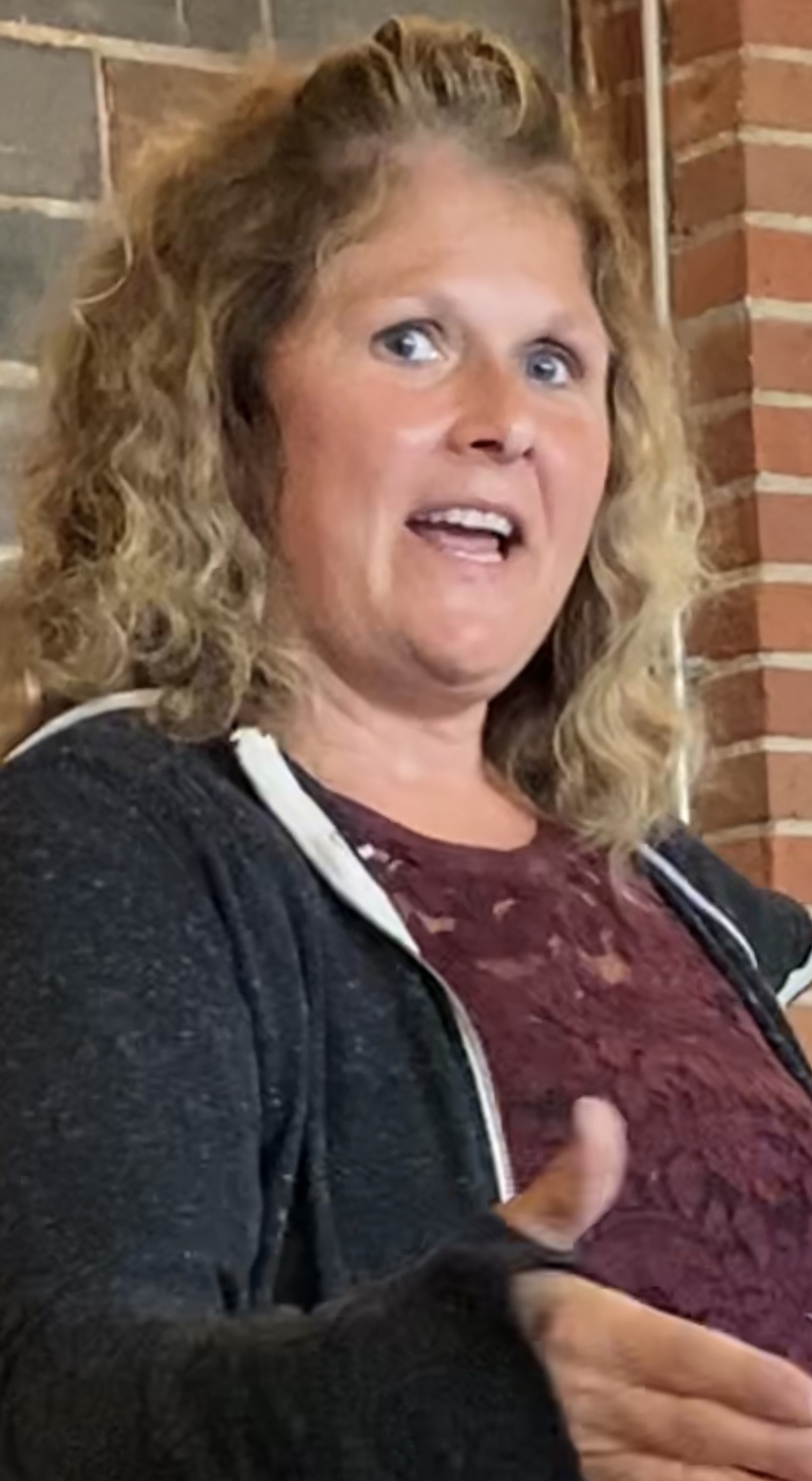

Becky Gonnerman, Luverne, describes her job during the pandemic as “a nightmare.”

Gonnerman, a nurse in health services at Smithfield Foods in Sioux Falls, spoke to a gathering at Take 16 Tuesday, Aug. 17, for the Rock County Farm Bureau annual meeting.

“We care for a lot of people,” she said about the packing plant where 3,700 employees process 19,500 hogs per day.

That was before February 2020 when COVID-19 began sickening people at the plant.

Pre-covid, Gonnerman tended to workers’ overall health — conducting hearing, vision and pulmonary function tests, along with drug tests and dressing the occasional wound from sharp equipment on line.

She works with a small team of health and safety professionals who navigate a diverse workforce that speaks 70 different dialects.

“So, communication barriers are huge,” Gonnerman said, adding that she’s had the privilege of knowing workers with families all over the globe.

Unfamiliar language and culture, as it turns out, became the hardest part of controlling COVID-19 once it entered the plant.

“Some are in one- or two-bedroom houses with multiple families,” she said. “It’s very difficult for some of these people.”

First signs and symptoms

“Covid started for us like everyone else,” Gonnerman said. “In late February people were starting to get symptoms.”

To breach the language divide, she said they put posters on the wall with illustrations of people coughing, and they marked big X’es on the floor to keep people apart.

“We trained managers to ‘please instruct your people to go home if they have symptoms.’ Anybody who’s coughing and anybody who’s not feeling well, get them out of here,” Gonnerman said, adding that employees were paid to go home if they were sick.

But the urgency of the situation was hard to convey.

“We have three cafeterias with round tables. We put barriers between them so only four could sit at a table, but we found them doubling up, hugging each other, not understanding,” Gonnerman said.

“We tried, we really tried, but the communication just wasn’t there. … And how were we supposed to tell them their culture has to change? They didn’t understand this was a pandemic. And that made it very difficult.”

Protective measures

Gonnerman said she and her colleagues implemented measures to stay safe.

“It’s not a locked facility, but you have to ring a bell to get into health services,” she said.

“We put a telephone in the entryway so everyone had to call us. We could see them, and if they had symptoms, we were doing their intakes and telling them to get out.”

This prevented her and the other staff from coming into direct contact with sick workers, but they struggled to keep up with ever-changing CDC recommendations.

“There were times when we were assessing someone in the entryway, and then quickly cleaning it, fogging it, washing our hands,” Gonnerman said.

“And that’s all you did. One nurse was on the phone, and the other was cleaning.”

Their work, at times, seemed futile.

“We’d get the call that someone was positive, and we’d have to call the plant to ask the manager ‘Who do they work beside? Who called safety? Who was their locker beside?’” she said.

“We’d have to go out and clean their locker and try to get these people in there at the same time people were coming down sick.”

‘We just couldn’t manage’

Gonnerman described the situation as a vicious cycle. It was 12 hours a day for weeks and months until we shut down. We just couldn’t manage it.”

She said it was frustrating to not be able to help people despite her efforts.

“The most difficult part of it was the phones,” Gonnerman said. “I would go to bed just exhausted from 12 hours of listening to the phone … listening to sick people coughing at you and all kinds of people in the background because you know they live in a tiny little house or apartment with kids running around.”

She said she’d tell them to quarantine in a room by themselves, but they didn’t have that kind of space in their homes.

“I think the worst part of it was my mom called one time and said people were really worried about me. I told her I’m fine. It’s the people I’m talking to every day, and they can’t quarantine because they don’t have a choice. They’re stuck in a one-bedroom apartment,” she said.

“I’m traumatized by listening to it. … Like any other nurse, it wasn’t fun. It was very, very difficult.”

Then, at the end of her workday, she’d return home where people feared she might be contagious.

“There was a time when I was a walking virus in Luverne,” Gonnerman said. “That is a nightmare I don’t want to go back to.”

‘It was eerie, very eerie’

The Smithfield office staff, too, were leaving — either because they had symptoms or had to quarantine due to exposure to someone with the virus.

“It was eerie, very eerie,” Gonnerman said. “I went over to HR one day and not a soul was there. … When I was the only one left sitting in health services answering the phone, and the benefits lady was the only one left, we had temp agencies coming in helping us.”

The situation in the plant was just as eerie.

“I don’t know much about the hogs or the business side of things, but I do know when I came into the plant to check my AEDs and I saw no hogs hanging in the hog kill, I saw no workers on the line, I saw maintenance painting and cleaning …. This wasn’t right, not right at all.”

Yet, Gonnerman didn’t contract the virus.

“I never got sick one time,” she said. “Never had one day off.”

Of the 3,700 workers employed at Smithfield, 1,294 were infected and four died, according to figures supplied by OSHA. In April 2020 the plant accounted for a large majority of total coronavirus infections in the state of South Dakota.

Paperwork, paperwork

Returning everyone back to work when the Smithfield plant reopened was also challenging.

“Every single person that was positive had to have an envelope of all these things: Who they had lunch with, what cafeteria they ate at, where they bought their groceries, where they went to the Laundromat, who was beside them in the locker room. … it was trying. It was very trying.”

She said she’d go through piles of releases from the department of health to see who could return to the plant after they’d quarantined.

“We wouldn’t let anybody come back to work unless we got a release from the department of health,” Gonnerman said.

Now, she said, she’s busy administering tests for people with symptoms. If they’re positive, they need two negative tests before they can return.

Also, health services staff at Smithfield have begun administering the COVID-19 vaccine. That, too, has required education and communicating over language barriers, but Gonnerman said about 200 had received the vaccine so far.

New normal

“It was a long time before I could do a hearing test again,” she said, referring to her pre-pandemic responsibilities.

Slowly, the Smithfield processing plant has geared back up, but not to pre-covid production.

“Pre-covid we would harvest 19,500 hogs daily. We were off for about three or four weeks,” Gonnerman said. “When we came back, we were harvesting 14,000. Now we’re at about 18,000, so we’re getting there.”

She said many of the 60-year-olds and older didn’t come back, and the same was true for some employees with compromised health.

And some of the pandemic barriers will likely remain.

“Now there are dividers between all workers on the production line. I don’t know if that will ever go away,” she said. “I don’t know that it should go away. It’s just going to help during cold and flu season.”

Gonnerman concluded by saying she finds her work rewarding, despite the pandemic experience.

“I tell you what. I love my job,” she said. “Those people —they love anything you do for them. For the most part, I try to tell them I appreciate them.”