,

,  ,

,

Three recent easements within the wellhead protection area that supplies 75 percent of Rock County with drinking water are expected to result in the biggest drop in nitrate levels in decades.

At 294 acres, the John and David Piepgras’ Minnesota Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (MN CREP) enrollment accounts for more than 10 percent of the highly vulnerable wellhead protection area bordering the Rock River.

It was seeded into permanent cover this spring, and final agreements are in the works. Two more landowners each enrolled 40 acres in Reinvest in Minnesota (RIM) wellhead easements. That land will be seeded this fall.

The total acreage — and location adjacent to two of the highest-producing wells — is significant, according to Rock County Rural Water director Ryan Holtz.

“This is where most of our water that we produce comes from. We believe it is a huge impact,” he said

Arlyn Gehrke, engineering technician for the Rock Soil & Water Conservation District, said permanent native grass cover is the key.

“Planting perennial vegetation was what really dropped the numbers in the wells,” he said of past work — including different types of easements and changes in farming practices.

Measurable progress over time

The first conservation easements within the wellhead protection area were recorded in 1994, and 20 years later the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and the Minnesota Department of Health offered cash incentives for reduced nitrogen application.

Farmers successfully changed the way they applied nitrogen fertilizer. They planted cover crops, and collectively it made a difference.

Replacing row crops with native grasses remains the fastest and most effective way to decrease nitrate levels.

The Piepgras brothers’ first easement, a 40-acre CREP enrollment seeded with native grasses in 2006, reduced Well 14’s nitrate levels by about one-third ─ from about 11 ppm to 7 ppm.

After their second easement, a 20-acre RIM enrollment in 2010, testing showed Well 14’s nitrate levels between 4 ppm and 5 ppm ─ roughly half of the original levels. Over the course of a year, nitrate levels now average 6 ppm to 8 ppm.

“Ever since, we’ve been working on getting permanent easements on the rest of these wells,” said Doug Bos, assistant director of Rock County SWCD/Land Management.

The coarse and porous soils cause any nitrogen that does leach to reach the aquifer quickly. Taking the land out of production meant nitrogen was no longer being applied. The grasses buffered the well from runoff.

Gehrke said he expected nitrate levels to drop within two to three years as a result of the most recent easements.

“We need to make sure that these wells stay at the level they’re at or drop in nitrates because our demand is always going up,” Holtz said.

Some of that demand comes from younger farmers attempting to get their start in farming by raising livestock. Bos said their first step is to see if RCRW can supply enough water.

“The economic impact for Rock County Rural Water to our county — I don’t want to say it’s immeasurable, but we have difficulty finding good quality water for our young farmers,” Bos said.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s standard for nitrate in drinking water is 10 parts per million. Nitrate levels are more than twice that in some of the 11 wells serving Rock County Rural Water’s 3,000 customers. Levels in individual wells range from 1 ppm to 25 ppm.

Last year RCRW supplied its customers with about 300 million gallons of water. The three wells capable of producing half of the water can’t be used because their nitrate levels are too high. RCRW mixes water from the wells to keep nitrates at acceptable levels.

It also purchases water from the South Dakota-based Lewis & Clark Regional Water System.

Making a difference

“It was a bona fide opportunity to contribute something meaningful to wildlife and soil and water protection,” John Piepgras, 82, said of the 2006 enrollment.

He and his brother, David, followed their 2010 RIM easement with the most recent, recorded in 2018, which put all but 80 acres of the farm into easements.

“Clearly, our No. 1 objective was to participate in a meaningful program of conservation,” John Piepgras said. He ticked off the benefits: It was an opportunity to improve the water supply, prevent soil erosion, increase wildlife diversity and preserve hunting land.

John Piepgras, whose career was in engineering and business, lives in the Chicago area. David Piepgras, 80, a consulting neurosurgeon at Mayo Clinic, lives in Rochester.

The Piepgrases grew up in Luverne. They inherited the land from their father, Elmer, whose boss at the grain elevator left him a farm in the 1980s.

The longtime renter, who with his family has lived on and farmed the land since the Piepgrases acquired it, suggested the initial easement, and will continue to live onsite and manage the property.

David Piepgras said he was concerned about nitrates, especially after seeing aquifer maps.

Over time, changing farming practices and intensive row-cropping had exacerbated nitrogen-carrying runoff. A couple of years of unusually heavy rains, low yields caused by flooding and low commodity prices prompted the brothers to take stock.

“John and I started to get the message that maybe we could do something better with that land than planting corn and beans on it,” David Piepgras said.

The easements compensate farmers for land taken out of production.

Boss said conservation programs have also motivated landowners to do more.

“Without RIM and CREP we would not be able to offer adequate financial dollars,” Bos said. We looked at a couple of other easement options and there wasn’t enough dollars per acre to make it attractive.”

In the case of the two 40-acre easements, RCRW agreed to buy the land after it was enrolled.

Forty-two people own land within the highly vulnerable wellhead protection area. Ten easements totaling 667 acres, made possible by nearly $2.5 million in state funds, have been enrolled to date.

The three most recent and pending easements are made possible by a combined total of $4.4 million in state and federal funds.

“Our goal is (to enroll) enough area in permanent grass to provide clean water,” Bos said.

'It's getting back into agriculture: It's the people'

Water Sources:

Rock County Rural Water serves about 75 percent of Rock County, including the towns of Beaver Creek, Hills, Kanaranzi, Magnolia and Steen. It pumps water from 11 shallow wells to 800 connections serving about 3,000 people.

Last year RCRW produced about 300 million gallons. It mixes water from its wells to ensure nitrate levels remain below the limit of 10 parts per million. That Minnesota Department of Health risk limit is based on the concentration deemed safe to consume daily over a lifetime.

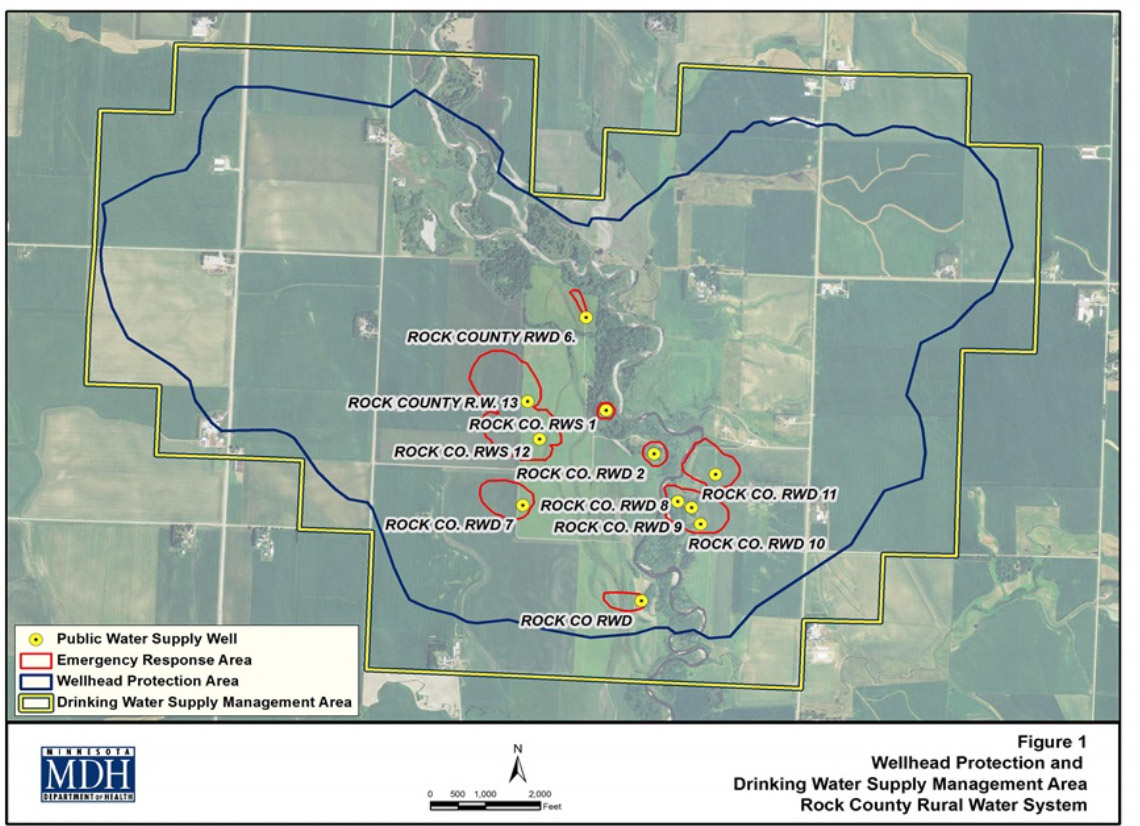

Protection area: The Minnesota Department of Health mapped the 4,500-acre drinking water supply management area. It borders the Rock River and includes a 2,706-acre highly vulnerable wellhead protection area.

MN CREP: The voluntary Minnesota Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program targets environmentally sensitive land in 54 counties in southwestern Minnesota.

Landowners enroll in the federally funded Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), administered by the USDA’s Farm Service Agency for 14-15 years.

They simultaneously enroll that land in a state-funded, BWSR-administered perpetual conservation easement. The land remains in private ownership. It is not open to public hunting.

Environmental considerations:

“For my brother and me and the farmer who’s on (the land), the environmental considerations as well as realities of markets and farming and what’s happened in recent years in terms of flooding — it just made sense,” David Piepgras said about their reasons for enrolling land within the wellhead protection area into a MN CREP easement.

“I suppose if it was all about money, and you wanted to sell it in parcels, that would have been a consideration. … I think the environmental gain, protecting the water, the state of farming now — we’d had a couple of floods a year or two ago when the corn crop flooded out; another year the beans flooded out.

“Some of it was outstanding farmland and some of it was becoming more marginal related to environmental changes, the weather, more rain, 100-year floods.”